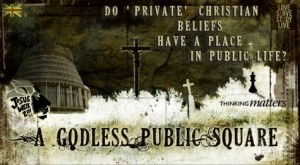

A few weeks ago, as part of Jesus Week at the University of Auckland, Thinking Matters and Evangelical Union hosted an event entitled A Godless Public Square: Do ‘Private’ Christian Beliefs Have a Place in Public Life? This event was a conversation between Theology, Philosophy and Law and featured Matthew Flannagan – Analytic Theologian, Glenn Peoples – Philosopher and Madeleine Flannagan – Legal Scholar. The video is still being edited and will be available soon but for now, this 3-part series comprises the written speeches of each speaker.

A few weeks ago, as part of Jesus Week at the University of Auckland, Thinking Matters and Evangelical Union hosted an event entitled A Godless Public Square: Do ‘Private’ Christian Beliefs Have a Place in Public Life? This event was a conversation between Theology, Philosophy and Law and featured Matthew Flannagan – Analytic Theologian, Glenn Peoples – Philosopher and Madeleine Flannagan – Legal Scholar. The video is still being edited and will be available soon but for now, this 3-part series comprises the written speeches of each speaker.

Glenn Peoples – Philosophy

Often the subject of religion and politics is alluded to by way of references to terrorism, vigilantism, totalitarianism and persecution, as though these are the only alternative to a public square stripped of religious conviction altogether. This is about as helpful and honest as the automatic association of secularism with the purges of Stalin. The truth is that the flourishing debate in the Western world over the legitimate role of religious convictions in our public decision making is set within the broad liberal democratic tradition. Within that tradition, taking for granted things like freedom of religion, freedom of speech, clear institutional separation of church and state, freedom of association and so on, we’ve seen that it is clearly possible to hold a variety of views on the proper place of religious belief in politics, policy, public lobbying, your own voting and so on. Of course, there are plenty of religious people in the world and in history who do not cherish liberty and mutual respect (as there are and have been non-religious people who do not cherish these things), but you and I do.

Our popular level discussion here in New Zealand over the proper role of religion in a free society – in the media, in letters to the editor, on talkback radio, in religious speeches, could have been greatly benefited by an exposure to the way that this issue has been dealt with in philosophy, specifically in political philosophy, in ethics and philosophy of religion, which are the areas that really interest me. In particular the following issues need to be seen as central: What is the specific concern that justifies people in identifying religious convictions as an area of worry over and above other convictions? Are these concerns applied consistently and fairly when not thinking in terms of religious convictions? Are they the right concerns to have about public life generally? Secondly, should these concerns really cause us to reconsider the role of religious convictions at all? If so, then how?

Why is religion singled out?

Conflict and Polarisation

Why is there an issue centred specifically around religion in the public square? We don’t hear much, if anything, about the worry of acting on our political beliefs or (usually) our ethical convictions or our scientific findings – at least not because they are political beliefs, ethical convictions scientific findings, yet there is a concern about religious beliefs in the public square, and that concern exists because the beliefs in question are religious. What makes religion special?

Perhaps the more popular reason that people might have for wanting to see religion take a back seat when it comes to public reason is that, in their view, religious beliefs unleashed in public are dangerous in certain ways. American philosopher Robert Audi is not alone in voicing the concern that “religious disagreements are likely to polarize government” leading to irresolvable disputes and political stand-offs.[1] In order to avoid strong polarisation and the associated mischiefs that come with it (lack of co-operation, social unease and mutual suspicion, perhaps even rioting and acts of violence or terrorism as in Northern Ireland), let us keep our religious beliefs well away from our political reason.

Matt has already said a thing or two about this, so I’ll just be brief. Is this fair? For starters, is it really true that as soon as we allow people to lobby, vote or even legislate in certain ways because of their religious convictions, we will witness intractable political stand-offs and social disorder? Not at all. We can easily imagine scenarios in which one person or group lobbies for a given policy because their religious convictions motivate them to do so, and another person or group lobbies for exactly the same policy with quite different motives. I think, for example, of the government’s role in marriage. I know of religious people who maintain that the state has no role in formalising marriage since this is, in brief, “God’s business” that the government should frankly stay out of as a matter of the purity of marriage as a holy institution. I also know of libertarians committed to the doctrine of self-ownership and the priority of personal liberty who also think, without any reference to God, that marriage properly belongs entirely to the private realm. So it can’t be the case that endorsing policies because of one’s religious convictions will inevitably or always lead to social or political polarisation and conflict.

That said, it’s true that different religious convictions (including convictions against religious beliefs) have led to considerable differences of opinion over public policy. But this does not show that this polarisation is relevant in deciding whether or not people should endorse policies for religious reasons. In order to assess that, we must ask: Is religious belief in any way unique because it often perpetuates the kind of polarisation lurking behind this fear? I do not see that it is. The last century of western history alone proves fairly conclusively that human societies can become polarised with no help from religion. Civil and political clashes between fascists and communists, for example, did not take place because someone was smuggling their religious beliefs into politics. On a somewhat less dramatic scale, I see no end to disputes in New Zealand over the rights bestowed upon Iwi by the Treaty of Waitangi, nor to the hostile attitudes in society that get stirred up by these stand-offs. Again, these disputes did not arise because of the clandestine combination of religious convictions and political lobbying. What is more, there is no reason to think that policies that are likely to polarise should never be advocated. It is easy for us to appreciate, for example, that the attempt to ban slave trading in the British Empire was intensely polarising, and yet we admire those who advocated abolitionist policy.

So firstly, making political decisions because of our religions convictions does not necessarily cause polarisation and conflict and secondly, even where it does cause polarisation, religion cannot legitimately be singled out as the culprit since politics in general can have the same effect – an effect which does not necessarily indicate that the policy being advocated should not be advocated. So if there is something basically wrong with bringing our religious convictions into the public square, it is unlikely to be because this practice results in social polarisation and conflict.

Two Concerns: Respect and Justification

Most political philosophers realise that if there is a principled reason for keeping religious convictions separate from politics, it will not be the pragmatic reason suggested above. A more sophisticated and arguably more plausible line of argument has been developed in various forms in the literature.

The argument starts, not with religion, but with very general principles in political philosophy. One of the crucial concepts of the modern western liberal democracy is that of equality. There is no politically privileged class. This affects the way our societies function in all kinds of way. It’s why we have the slogan one man, one vote. Everybody’s voice counts the same. It’s why women and men both vote. But the principle of equality and consequently of equal respect is more pervasive than that. It’s the reason you care – or should care – about the way your fellow citizen is treated, politically speaking. Just as you don’t want to be subjected to arbitrary legal coercion for which there is, as far as you are concerned, no good justification, you also don’t want your fellow citizen to be treated that way either. Because we’re all equal, your fellow citizen, no less than you, is owed an explanation for why he or she is subjected to the laws that she is being asked to live by.

In short, the policies that you advocate need to be justified to your fellow citizen in the right way, or else you’re just coercing them and you’re not showing them proper respect as your equal.

20th century political scientist Jown Rawls introduced the term overlapping consensus to describe the sorts of policies that are appropriate in a liberal democracy. Basically, the idea is that there are policies that are justified to you – justified by your own desires, beliefs, values goals, and so on. But of course the fact that they are justified to you doesn’t make them justified to anybody else. Everybody has their own set of beliefs, values, desires and so on, and their set makes a set of policies justified to them. Think of everybody’s set of justified policies as a large circle. Although it’s clear that these circles won’t share exactly the same outlines – because the liberal democracy is marked by pluralism – the fact that we share basic values, says Rawls, means that there will be considerable overlap. Think of all of us as a circle of beliefs, desires and values, and the area where we overlap in the middle is the area where those beliefs, values and desires overlap enough to support the same policies. There will, said Rawls, be an overlapping consensus on a range of policies. Those policies will be justified to all of us. To use Rawls’s language, there will be a consensus among reasonable citizens on a set of overlapping policy ideals, and it is those policies that meet the standard of justification that properly expresses respect for all our fellow citizens.

20th century political scientist Jown Rawls introduced the term overlapping consensus to describe the sorts of policies that are appropriate in a liberal democracy. Basically, the idea is that there are policies that are justified to you – justified by your own desires, beliefs, values goals, and so on. But of course the fact that they are justified to you doesn’t make them justified to anybody else. Everybody has their own set of beliefs, values, desires and so on, and their set makes a set of policies justified to them. Think of everybody’s set of justified policies as a large circle. Although it’s clear that these circles won’t share exactly the same outlines – because the liberal democracy is marked by pluralism – the fact that we share basic values, says Rawls, means that there will be considerable overlap. Think of all of us as a circle of beliefs, desires and values, and the area where we overlap in the middle is the area where those beliefs, values and desires overlap enough to support the same policies. There will, said Rawls, be an overlapping consensus on a range of policies. Those policies will be justified to all of us. To use Rawls’s language, there will be a consensus among reasonable citizens on a set of overlapping policy ideals, and it is those policies that meet the standard of justification that properly expresses respect for all our fellow citizens.

Before you support any policy with your vote – your voice as a citizen, Rawls says, it must be one that is justified to everyone else. The devil, however, is in the details. Rawls stressed that we’re only interested in the policies that our fellow citizens support in light of their reasonably held convictions, goals, values etc. And which beliefs, values, goals etc are reasonable? As good supporters of the liberal democracy, we don’t think racism is a reasonable set of values – or sexism. But what about socialism? Or strong views on private property rights and individualism? Or – and here’s where things get interesting – what about atheism? The father of classical liberalism, John Locke thought that atheism was such a despicable and dangerous view that it shouldn’t even be tolerated in a modern democracy. Or what about Islam? Or Buddhism? Or Christianity?

Part of the respect that is promoted in the modern liberal democracy is that we are accepting of pluralism. We don’t try to change the fact that we have pluralism, we accept that other people inhabit different circles and they are welcome to do so. Provided we take this open minded approach to what counts as a reasonable outlook, without imposing our beliefs upon others, the actual ground on which all those circles overlap starts shrinking.

Political philosopher Gerald Gaus was stating the obvious – even if slightly exaggerating – when he said “little, if anything, is the object of consensus among reasonable people.”[2] We recognise the danger in deferring too much to our fellow citizen, in a sense, showing them too much respect. If we give up our support of a policy just because there exists, somewhere, a reasonable person who doesn’t currently support it, the democratic state is likely to be paralysed. What about same sex marriage? Which way should the law go? Should we use trade tariffs? Should charitable organisations – like churches – be tax exempt? Should churches be treated like charities? Should manufacturers and producers be required to regulate their business activities to take account of public concern over global warming? Is there a total consensus of reasonable people on any of these issues one way of the other? In fact there is not, and yet we do have policies one way of the other on these things, and we really can’t help doing so.

Let’s not swing too far the other way. We do want to respect our fellow citizens and not just coerce them with our will. But we have no power over what they accept and don’t accept. Justifying our policies to our fellow citizens in a way that treats them with adequate respect cannot mean that we can’t propose any policy that they don’t accept already. Just imagine advocating a policy on abortion only if it was supported both by those who believe in the sanctity of human life from conception and those on the extreme end of the pro-choice side of the issue, who think that even if the unborn child is a human person in the full sense, a mother has the right to terminate pregnancy at any stage. Good luck.

But if you don’t have to successfully convince people that your policy is the right one in light of what they believe and value, then what do you have to do? According to Gaus, and I think this moves us in the right direction, you have to idealise. You idealise or imagine away from what your fellow citizen is right now willing to accept, and you think of what, as far as you can tell, they – given what they now believe about reason and evidence – would accept if they were better informed and willing to fairly consider all the available reasons. As Gaus puts it when considering our hypothetical fellow citizen, Alf, to whom we owe a justification, “if Alf’s beliefs were subject to extensive criticism and additional information, does his viewpoint commit him to revise his beliefs?”[3] If so and if we offer reasons for him to think so, then we are doing our duty in terms of showing Alf that what we are proposing really does have something going for it. So according to this view, you’re not hamstrung by what your fellow citizen is currently willing to endorse. At the same time, you regard them as worthy of a justification and you offer them one in good faith – one that you are justified in believing that they should accept based on what they know and are capable of coming to understand, but recognising that they may in fact not accept it.

Where does this leave religion?

Once we’ve strengthened the notion of political justification to make it plausible and workable, we’ve got to sit back and ask, “OK, now does this actually leave us with any problems for policies that we support for religious reasons.” Take my stance on abortion or on marriage. Let’s say that I hold to my views on those issues for religious reasons – reasons that ultimately involve my beliefs about what God wants. Does that automatically mean that there is no form of justification that I could offer for those policies? Maybe – if we are pre-committed to the personal belief that there is no justification for any of these beliefs about God. If we assume that there are no reasons for our beliefs and hence our policies that we can give our fellow citizens, reasons that we reasonably believe that they should consider if they were open minded, willing to listen to reasons, consider all the arguments and evidence, and not reject considerations out of hand just because we’re talking about the supernatural.

But why assume that? To ask Christians to assume this is to basically ask them to assume that Christianity is intellectually indefensible. It may be that you think of religious faith as being irrational, unconcerned with reasons and basically being blind devotion. I regard that caricature as a symptom just the sort of ignorance and unfairness that modern secular liberals sometimes accuse religious people, ironically enough. Now, of course Christians realise that they aren’t going to successfully persuade everybody, just as defenders of a whole range of theories on ethics understand they aren’t going to actually persuade everybody, as scientists do also when it comes to one of their findings (but this should not stop them from urging people to support policies on, say, smoking, pollution or climate change). But to ask Christians to just assume that there exists no justification for their beliefs that they can offer is not neutral. It asks them to assume that at least some of their beliefs are false, namely their beliefs about just how defensible their beliefs are.

The fact is, the disagreement over whether or not any religious beliefs are properly justified is just as evident as the disagreement over religious beliefs themselves. To claim that religious convictions must not drive public reason, and to claim the justification test as our reason for this, is simply to take a controversial stance on religious matters. It is to veil an anti-religious bias in the name of neutrality.

In a liberal, pluralistic society, of course you are welcome to the private belief that all religious beliefs lack appropriate justification, and the belief that nobody should be convinced to hold them. But to require everybody else stay out of the political game altogether until they are prepared to live in accordance with that belief steps way over the line of what is acceptable in a free society. You are welcome to advocate policies that are compatible with your beliefs, as long as you are willing to engage your fellow citizen conscientiously, as an equal with you, only propose policies that are compatible with this doctrine of equality, and therefore genuinely offer your fellow citizen justifications for your policy that you think there are good reasons to accept. But to suppose that only people whose beliefs are not religious are morally permitted to do this is to manifest a kind of bigotry that has no place in a modern, pluralistic and democratic society.

Part III of A Godless Public Square: Do ‘Private’ Christian Beliefs Have a Place in Public Life? features Madeleine Flannagan’s talk from the perspective of Law.

[1] Robert Audi Religious Commitment and Secular Reason (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000) 39.

[2] Gerald Gaus Justificatory Liberalism: An Essay on Epistemology and Political Theory (New York: Oxford University Press 1996) 293.

[3] Ibid, 32.

RELATED POSTS:

A Godless Public Square: Do ‘Private’ Christian Beliefs Have a Place in Public Life? Part I Matthew Flannagan – Theology

A Godless Public Square: Do ‘Private’ Christian Beliefs Have a Place in Public Life? Part III Madeleine Flannagan – Law

If you want to hear more from Glenn on this topic he has made a very good podcast on this topic here: Podcast: Religion in the Public Square

Tags: Doctrine of Religious Restraint · Gerald Gaus · Glenn Peoples · Jesus Week · Religion in Public Life · Robert Audi · Thinking Matters19 Comments

A common objection to belief in the God of the Bible is that a good, kind, and loving deity would never command the wholesale slaughter of nations. In the tradition of his popular Is God a Moral Monster?, Paul Copan teams up with Matthew Flannagan to tackle some of the most confusing and uncomfortable passages of Scripture. Together they help the Christian and nonbeliever alike understand the biblical, theological, philosophical, and ethical implications of Old Testament warfare passages.

A common objection to belief in the God of the Bible is that a good, kind, and loving deity would never command the wholesale slaughter of nations. In the tradition of his popular Is God a Moral Monster?, Paul Copan teams up with Matthew Flannagan to tackle some of the most confusing and uncomfortable passages of Scripture. Together they help the Christian and nonbeliever alike understand the biblical, theological, philosophical, and ethical implications of Old Testament warfare passages.

I think that , of course, each should be able to have his or her own religious beliefs but there should never be an official religion of state. This is what is meant by separation of church and state. Government shall not establish religion—as it says in the US constitution.

This means the framers of the constitution wanted a government that was neutral as to religion. They realized that any state officially favoring one religion or sect over another would be a corruption of government, just as favoring officially, that is, government conferring prejudicial advantage permanently to Republicans over Democrats or vice versa would be a corruption.

The government may be run by people of different persuasions and be influenced by those persuasions–but the government itself is never designated permanently a Republican or Democratic government nor a catholic or unitarian nor atheist government.

The framers were only about 130 years away from the devastating period of religious wars in Europe –the sheer brutality and murder—

was still strongly in the mind of folks. And there were many sects in America who did not see eye to eye and who came to America for the religious freedom; freedom to worship without the persecution inflicted upon them by the official government church –Anglican–in England.

Seems to me the framers created a splendidly appropriate measure to guard against religious bigotry becoming an official element of US government. As a Christian I am in favor of this government neutrality–because the alternative sucks.

You need to read some history my friend.

“You need to read some history my friend”

Actually, the argument from religious wars was addressed in the previous post on this topic.

The false claim that the doctrine of seperation of church and state requires a separationist reading of the establishment clause – the separation of religion from public life – was actually addressed in Madeleine’s talk.

The phrase “seperation of church and state” is not actually in the US Constitution. It comes from a letter written by Jefferson shortly after the Founding. The Supreme Court did not start intepreting the establishment clause through this letter in this way until almost two-hundred years later.

I am convinced one of the problem here is that it was once thought that there was one ethical standard everyone could agree on in spite of their underlying philosophy (religious or non-religious). But we as a society are reaching a place where this is less and less true. Unless we can return to a consensus on the basics, we are left with trying to build a society in an atmosphere of divergent beliefs. Unfortunately it can sometimes seem easier to deny those you disagree with access to the public square rather than learning to live with the situation.

Religion is kept out of public life so we can debate more important things than abortion, jailing homosexuals and censoring books such as A Clockwork Orange. Religious people hate freedom and have a narrow view on ethics and therefore can not be part of a decent debate on how to run society.

And there were many sects in America who did not see eye to eye and who came to America for the religious freedom; freedom to worship without the persecution inflicted upon them by the official government church –Anglican–in England.

Your comment assumes that the modern take on what happened is the truth.

The reality is that most states actually *had* a state religion (or rather state denomination as we would say today). The reason the federal government didn’t have one is not because they thought it would be a bad idea, but rather that they couldn’t agree on which one to make it.

Dicky P: religion is in actual fact a very important part of public life.

When you say “Religion is kept out of public life” what you *mean* is that atheists are trying to keep views that have religious origons out of public life, which is in fact quite a different thing.

You say “Religious people hate freedom”. Nice to know. I guess the (for example) Polish Solidarity movement might have been surprised to know that.

“The reason the federal government didn’t have one is not because they thought it would be a bad idea, but rather that they couldn’t agree on which one to make it.”

so we should base our society on what we have in common, which means that if there are conflicting religious views one specific view should not be given any precedence over another? sounds great.

There’s a possible way to get around worries about privileging secular justifications over theological ones, and that is to split the difference between what actual reasonable people would agree to and what hypothetical reasonable people would agree to.

Of course it will be impossible to find anything that all reasonable people actually agree upon, and to discover what all hypothetically reasonable people would agree upon would require solving once and for all major problems of epistemology – an obviously dubious prospect.

Instead we ought to look at how rationality functions within institutions, and pick those institutions where consensus is as a matter of fact more easily achieved over those where it is not. The reason for this is that actual success in producing agreement is valuable, since politics is a practical activity and desirous of real rather than notional results.

The natural sciences are the obvious place to start. While scientists disagree a great deal over particular matters, science as an institution has broad agreement on the rules pertaining how differences are to be resolved. By this is meant the norms of science such as the necessity that experiments be replicable and so on. No human institution has ever managed to marshal this much agreement over method and by extension over fact. That makes the methods of the natural sciences an obvious place to start when looking at the evidential rules for a liberal society, since it is in actual fact successful at producing a basis of agreement.

In philosophy, agreement is going to be harder to find, given that discipline’s habit of doubting its own methods, but anyone who has done philosophy knows that despite the differences between philosophers – and these are often radical differences – it is possible for philosophers to agree on what is a good argument by the standards of the discipline. This is how it is possible for philosophers who wildly disagree about philosophical questions to agree on a grade for a paper they are marking. So even philosophy manages to marshal agreement among more or less all of its practitioners on basic questions of what makes a good and bad argument (the sorts of things you would find recommended in a critical thinking text book).

No such widespread agreement has ever been produced by theologians, except on a limited scale (say, the church of the high mediaeval period). It’s simply not very successful at producing actual agreements over method, and even less successful at producing consensual agreement over purported facts. One only has to compare sectarianism in religion with sectarianism in philosophy or the natural sciences to see that the former is deeper and more pervasive (similar in fact to disputes over the interpretation of art works).

That being so, if we are to construct a society based upon consent, it would behoove us to adopt rules that are the most successful in practice at producing group consent instead of holding out hope that everyone will become adherents of religions similar enough to generate such a consensus. A society that does this will be more successful, even if never perfect, at being a community of rational consenting persons.

A

You write

The natural sciences are the obvious place to start. While scientists disagree a great deal over particular matters, science as an institution has broad agreement on the rules pertaining how differences are to be resolved. By this is meant the norms of science such as the necessity that experiments be replicable and so on. No human institution has ever managed to marshal this much agreement over method and by extension over fact. That makes the methods of the natural sciences an obvious place to start when looking at the evidential rules for a liberal society, since it is in actual fact successful at producing a basis of agreement.

This disagreement falls apart when one asks questions about wether scientific realism or anti realism is correct, it also falls apart when you ask substantive philosophy of science questions such as what is the scientific method? What counts as scientific theory construction and so on.

Moreover, in many respects this is hopeless because scientific studies can’t give you normative conclusions and public policy questions are always normative questions about what law we should put in place, whats the just position to adopt and so on.

No such widespread agreement has ever been produced by theologians, except on a limited scale (say, the church of the high mediaeval period). It’s simply not very successful at producing actual agreements over method, and even less successful at producing consensual agreement over purported facts. One only has to compare sectarianism in religion with sectarianism in philosophy or the natural sciences to see that the former is deeper and more pervasive (similar in fact to disputes over the interpretation of art works).

This is false take the consensus you attribute to philosophy

“and these are often radical differences – it is possible for philosophers to agree on what is a good argument by the standards of the discipline. This is how it is possible for philosophers who wildly disagree about philosophical questions to agree on a grade for a paper they are marking.”

I think the same kind of agreement can be found within theology, in fact most of the consensus contemporary analytic philosophers use on what is a good argument is taken from historical theological discussions of logic anyway.

I doubt theologians are going to debate wether modus ponens is valid, or the criteria of a sound argument.

Of course there might be debates over hermenutical and epistemological questions but these are the same debates that occur within philosophy.

Moreover I doubt there is any greater consensus amougst secular philosophical ethics than there is in theological ethics. I made that point in my talk.

Government shall not establish religion—as it says in the US constitution.

Actually it says congress [the federal government] shall pass no law respecting the esthablishment of religion or restricting the free excercise thereof.

@A,

Surely it would be even easier to obtain a community of consenting persons by killing off everyone who disagrees with your political party?

The objective of a(n ideal) liberal democracy isn’t to obtain a consensus as easily as possible. It’s to determine what is good and fair based on the consensus of all individuals who have reasonable beliefs and perspectives.

If there exists justification for a person’s beliefs and hence the policy they wish to advocate, then their opinions and reasons should be considered. The problem is that there seems to be an assumption that religious people cannot produce any such justification and are thus morally obligated to keep their religious convictions to themselves, and out of the public square. This is an unfair assumption to make and isn’t consistent with the fundamental principles of a free society.

Hugh I question your statement;

“The problem is that there seems to be an assumption that religious people cannot produce any such justification and are thus morally obligated to keep their religious convictions to themselves”

Sure its common for one group of people to think that an alternative gorup cannot justify their claims.

Religious people think that of non-religious. Catholics of protestant, Left of right. And vice versa in all cases.

But a characteristic of a secualr democracy is that people are surely obligated to present their views. To contribute to the market of ideas.

That does not mean that others are obliged to accept those ideas. After all the ideas may just be silly. Alternatively others may not wish to consider them

But no-body is preventing religious peoiple from contributioing. Haven’t you noticed that they can be quite persistent, knocking on doors etc.

This idea that religious people are being prevented from colntributing, or even being persecuted, is just the whining of conservative relgious people who wish to have exemption from things like laws on discrimination, employment, etc.

Or their anguish when they find that ranting about their god does not iunfluence others.

”But a characteristic of a secualr democracy is that people are surely obligated to present their views. To contribute to the market of ideas….

But no-body is preventing religious peoiple from contributioing. Haven’t you noticed that they can be quite persistent, knocking on doors etc….This idea that religious people are being prevented from colntributing, or even being persecuted, is just the whining of conservative relgious people who wish to have exemption from things like laws on discrimination, employment, etc.”

Except that the leading political philosophers who defend secular liberal democracies, such as Robert Audi, Gerald Gaus, John Rawls, Stephen Macedo, Richard Rorty and so on, do say that religious citizens have a moral obligation to not present religious or theological reasoning in public debate, and none of these people are “conservative religious people” they are in fact the leading mainstream theorists of secular democracy. A fact documented by both Glenn, Madeleine and I. Moreover, important court cases have interpreted religious freedom laws this way, such as the Lemon Test which guided US supreme court decisions, again a case not decided by religious conservatives.

So Ken when you say that its only religious conservatives who claim this, and they have made it up to whine. You are clearly and demonstrably wrong, moreover it had been pointed out to you repeatedly that this is the case.

Ken,

Could you please provide your definition of “The Public Square”? (Are you aware that this is NOT THE SAME as “in public”?)

You are consistently misunderstanding this term across threads and hence attacking strawmen. I’ve seen Matt, Mel and Glenn attempting to bring this to your attention but for some reason it always escapes you…

From the Stanford Encylopedia article on religion and political theory.

1. The Standard View

The standard view among political theorists, such as Robert Audi, Jürgen Habermas, Charles Larmore, Steven Macedo, Martha Nussbaum, and John Rawls is that religious reasons can play only a limited role in justifying coercive laws, as coercive laws that require a religious rationale lack moral legitimacy.[2] If the standard view is correct, there is an important asymmetry between religious and secular reasons in the following respect: some secular reasons can themselves justify state coercion but no religious reason can. This asymmetry between the justificatory potential of religious and secular reasons, it is further claimed, should shape the political practice of religious believers. According to advocates of the standard view, citizens should not support coercive laws for which they believe there is no plausible secular rationale, although they may support coercive laws for which they believe there is only a secular rationale. We can refer to this injunction to exercise restraint as The Doctrine of Religious Restraint (or the DRR, for short).[3] This abstract characteization of the DRR will require some refinements, which we’ll provide in sections 2 and 3. For the time being, however, we can get a better feel for the character of the DRR by considering the following case.

The article contains links to primary sources.

So according to the leading peer reviewed encylopedia on philosophy, published by Stanford University, the position Ken says is made up by religious conservatives to whine is in fact the “standard view” of main stream political theorists of liberal democracy.

Perhaps Ken should inform himself of topics before he writes on them.

Matt – you’re confusing one discipline with another. In practice, scientists almost never care about whether realism or anti-realism is correct. Those are largely philosophical questions, divorced from the everyday practice of the sciences, which is to borrow a phrase from Richard Feynman: “shut up and calculate”.

The natural sciences do not yield normative conclusions, but I never suggested that they did. The point in question was about limning the bounds of respectable public debate, but public debate is often not about norms, but about claims of fact (example: whether human forced climate change is real). Normative questions can be left over for philosophers, although there will be greater scope for disagreement in method there, in a way that there is not in the natural sciences (example: scientists generally do not question the need for replicability of experiments).

“I think the same kind of agreement can be found within theology, in fact most of the consensus contemporary analytic philosophers use on what is a good argument is taken from historical theological discussions of logic anyway.”

Your error here is to again confuse disciplines. Aristotle is not a theologian in the modern sense of the term, nor is logic the province of theology. It is part of philosophy that is utilized by other disciplines, but genuinely the object of the disciplines of philosophy and mathematics. As you say:

“I doubt theologians are going to debate wether modus ponens is valid, or the criteria of a sound argument.”

That’s my point. These things are suitable rules for conducting public debate by, unlike practices such as shamanism or divination. Revealed theology is not.

My point is not that there is substantive agreement in philosophical ethics, but that there is general agreement on the rules of debate and what counts as winning or losing an argument. Moreover, the general spread of such standards in the academy and in everyday debate, along with the fact that they are robust enough to withstand criticism, makes them, along with the scientific method, good candidates for public reason. It would be absurd if public reason only allowed deontological arguments, for example, because there is no widespread consensus that these are the correct form of moral argument. Similarly, it would be ridiculous to allow theology, since there is no such widespread agreement among theologians about specifically theological truths (there may be consensus about hermeneutical methods, but hermeneutics is a distinct branch of knowledge than theology).

Your arguments require confusing disciplines. Theology qua theology cannot command the widespread consensus that some other disciplines do, which makes it a poor candidate for public rationality.

@ Hugh

“Surely it would be even easier to obtain a community of consenting persons by killing off everyone who disagrees with your political party?”

Yes, but it would be undesirable for all sorts of obvious reasons.

“The objective of a(n ideal) liberal democracy isn’t to obtain a consensus as easily as possible. It’s to determine what is good and fair based on the consensus of all individuals who have reasonable beliefs and perspectives.”

That last clause makes me think that you aren’t on the same page as Matt, Glenn or myself. The point of Rawls’ theories and other theories of the public sphere is to find a way of determining what counts as a reasonable belief or perspective. Matthew is arguing that this should be extended to include religious reasons. I am (for the sake of argument, because I don’t believe in Enlightenment political philosophy myself) arguing the opposite. We aren’t arguing about consensus per se, but about the specific consensus on what counts as reasonable beliefs and perspectives.

“The problem is that there seems to be an assumption that religious people cannot produce any such justification and are thus morally obligated to keep their religious convictions to themselves, and out of the public square. This is an unfair assumption to make and isn’t consistent with the fundamental principles of a free society.”

To assume that religious people cannot produce such justification would require, as I argued above, solution of some very pressing epistemological problems. But the alternative is worse: if people have radically incompatible beliefs about the constitutional basis of society (which is what Rawls is really talking about), then we segue from liberal democracy to mob rule. The point of Rawls’ work is to establish fundamental principles and rights that determine the basis of a just society.

The core element of that is that nobody should ever be subject to a rule that they could not in principle verify for themselves. Otherwise we end up with situations where people will say things like: “The powers of the universe told our group that everyone else should lavishly fund our lifestyle, but they speak only to us, but they made it clear that you should all do what they say”. That might sound funny, but almost all ancient civilizations more or less operated on that rule, with a priestly caste living off of everyone else’s labour.

Matt is correct that it seems odd to say that a religious claim must necessarily not be something that someone could in principle verify the truth or falsehood of for themselves. That would indeed prejudge the issue. On the other hand, my argument was that making verification in principle was a bad move. It would be more effective to take a pragmatic view and make it “public verification in practice”. Of course that would pay the price of allowing a religious monoculture to bring religious reasons into the public sphere, but we do not live in a religious monoculture, so it wouldn’t work for us. It would however, leave it open for religious thinkers to attempt to persuade the rest of the community of the validity of religious reasons (and even Rawls allows that), which leaves a back door for the religious community to bring religious reasons into public debate, as long as they first establish a practical consensus. In other words: establish the sort of widespread consensus that the natural sciences have, but about scriptural authority, and you can feel free to conduct public policy debates on scriptural grounds.

I’m not sure if the argument in the end carries the day, but it does seem to adhere to the spirit of Rawls, if not the letter.

Hugh, it’s not a matter of confusion – it’s a matter of humour and irony – which seems to be lost of some people around here. Although it gives them a naïve opportunity for diversion.

If you honestly believe I “misunderstand the term” – be specific. Vague accusations suggest you have not really considered the issue.

I have always understood “The Public square” as a metaphor to describe the interaction in a pluralist society of people with different ideas and viewpoints. No, I don’t understand it as a physical space at all – which should be obvious from my comments to anyone with literary skills.

Sure, governments and ethical conventions can limit interaction between people but in our society there is very little of that and certainly no government restriction on participation. Some people might insist that religion, politics, and sex not be discussed at parties.

Other people might attempt to limit criticism of religion (even at the UN level this has been interpreted as defamation of religion by the IOC). However, it is becoming increasingly accepted that religion is just as legitimate a topic of discussion and criticism as is politics and sport – despite the fact that some people get emotional.

I have made very clear my attitude is that I don’t support or subscribe to any such limitation. I don’t accept that Glenn, Matt or Madeleine do either.

The whining comes in because they pretend that the criticism some academics make of the use of religious arguments in public discussion is somehow martyring them. Silly, it would be like me saying that Matt, Madeleine and Glenn’s frequent demands that I do not comment on religion, philosophy , science, (or basically anything) because I do not have their specific academic training is somehow inhibiting me. It is not – it just makes them look silly because it comes across as an attempt to stifle, or cop out of, discussion rather than honestly participate in it. I am in the same boat as Dawkins on that – he ignores attempt to make him STFU (claims he had no right to produce “The God Delusion” because he is not an academic theologian for example). I similarly ignore similar demands on me.

My contribution to debate is my own responsibility – I am not blaming my approach on others or making myself out as disadvantaged.

Hugh – just seem this from Matt:

“Perhaps Ken should inform himself of topics before he writes on them.”

See what I mean. I could whine that Matt is somehow demanding that I not use my won arguemnts in discussion because they are not acceptable to him.

However, while I am happy to accept any criticism or correction (always ready to learn) I see that sort of approach from Matt as a sign of weakness on his part, especially when usually accompaneid by attempted diversion or tricks like his bait and swtich.

It certainly doesn’t stop me thinking or entering into discussion.