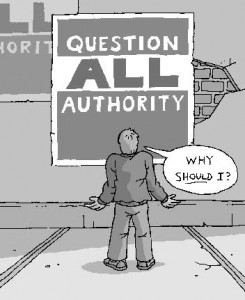

The ultimacy and decisiveness of reason is itself just as vulnerable as the existence of God. That one ought to “justify” one’s thought is to me just another religious-like commandment. If someone does not buy into the god-level authority of reason, especially pertaining to universal and ultimate domains of predication themselves, there is no possible logically prior inferential warrant.

The ultimacy and decisiveness of reason is itself just as vulnerable as the existence of God. That one ought to “justify” one’s thought is to me just another religious-like commandment. If someone does not buy into the god-level authority of reason, especially pertaining to universal and ultimate domains of predication themselves, there is no possible logically prior inferential warrant.

Only assuming logic and reason makes logical priority possible and necessary, so there is nothing possibly logically prior, in the sense of more inferentially basic, if logic itself is questioned. One can end up *appealing* to some kind of intellectual pragmatics, but that cannot be a *logical* appeal without simply begging the same question all over again: namely, whether logic or general reason have any god-like authority over one’s thinking.

And this is just as questionable in any other proposed authority. Hardly limited to the God belief. Sorry to dash a certain hope.

But these points and any other possible points that I might be making in this writing are themselves subject to the same problems, since they too depend on a wholesale acceptance of some core of a logical/rational ideal, nonlocal obligation relations between rational standards and each mind, the preferential value of inquiry, the decisive criterial status of reason, and so on.

But at that level what can be argued against them?

And what need is there to justify them?

A common objection to belief in the God of the Bible is that a good, kind, and loving deity would never command the wholesale slaughter of nations. In the tradition of his popular Is God a Moral Monster?, Paul Copan teams up with Matthew Flannagan to tackle some of the most confusing and uncomfortable passages of Scripture. Together they help the Christian and nonbeliever alike understand the biblical, theological, philosophical, and ethical implications of Old Testament warfare passages.

A common objection to belief in the God of the Bible is that a good, kind, and loving deity would never command the wholesale slaughter of nations. In the tradition of his popular Is God a Moral Monster?, Paul Copan teams up with Matthew Flannagan to tackle some of the most confusing and uncomfortable passages of Scripture. Together they help the Christian and nonbeliever alike understand the biblical, theological, philosophical, and ethical implications of Old Testament warfare passages.

This article is a bit too short?

Need some analogies to make it more fun to read

So what is it you’re actually saying ? If we don’t believe in God then we belong in a Monty Python sketch because it makes as much sense ?

Paul, that’s exactly what he or she saying. Or to paraphrase: because we accept the presupposition of reason and logic, we should accept the presupposition of god … and this same argument equally applies to the Great Pumpkin, fairies, the invisible dragon in my basement and whatever other supernatural nonsense you might be inclined to believe in. Which begs the question of why the existence of God is more likely than the Great Pumpkin, fairies, invisible dragons, etc. I’m still waiting for Plaintinga & MandM to explain that one. WLC relies on the Holy Spirit to reveal the truth to him. But wait … truth requires the presupposition that we can reply on reason and logic. Oh, oh – I think we’ve entered a perpetual loop.

“because we accept the presupposition of reason and logic, we should accept the presupposition of god”

I don’t recall making this argument.

Atheist Missionary,

Plantinga’s not your man, Van Til is. The transcendental arguments for God’s existence undercut epistemic justification by showing that only a universal rational being can provide the pre-conditions for logical debate, empirical inquiry (which assumes the universe behaves with regularity), etc.

TAG attempts to show that, prior to debating whether God belief is rational, we have already either accepted it, or else if not we have a defeater. How can one believe in normative logical operations sans a universal mind? You can’t. So, they are just descriptive of brain states. And then they aren’t universal.

David Parker wrote:

“How can one believe in normative logical operations sans a universal mind? You can’t. So, they are just descriptive of brain states. And then they aren’t universal.”

What do you mean by ‘normative logical operations’ ?

Are you proposing that the Law of Identity, Law of Non-Contradiction and Law of Excluded Middle are Absolute Laws that evidence the existance of the Christian God (and only the Christian God) ?

And yes, I am teeing you up.

Paul Baird,

To simply state it: logic is normative if it prescribes standards for thought and reasoning.

“Are you proposing that the Law of Identity, Law of Non-Contradiction and Law of Excluded Middle are Absolute Laws that evidence the existance of the Christian God (and only the Christian God) ?”

No, I am proposing that these features of the universe–if they exist, and are not mere preferential conventions that humans have invented, or else descriptions of the way human brains operate–presuppose something which contradicts naturalism. They presuppose a divine mind.

Swing away! 🙂

Ok, I was expecting absolutism 🙂

Anyways – why does normative logic specifically presuppose any God and in particular the Christian God ?

Paul,

A prior question is why should there be *any* universal normative statements at all, if there is no God?

Can we both agree that that the answer to this prior question is, “there is not one particle of evidence that there should”? If so, then it follows plain as day that telling someone they “ought to be reasonable” and drop their beliefs about God is utterly groundless. What is this normative standard that compels agents to be rational. What justified the claim that *anyone* including Paul Baird, *should* do anything?

You asked, “why does normative logic specifically presuppose any God and in particular the Christian God ?”

First, since I’m not a primary scholarly source, let me direct you to an essay by James Anderson entitled, “If Knowledge, Then God.” (link)

He examines the views of Plantinga and Van Til in more depth than I should attempt here.

As you’ll recall, I drew distinctions regarding logical laws: as descriptions of brain states (functions), as human conventions, and as universal norms.

Your question implies the third. My answer asserts the impossibility of the contrary. It seems as plain as day to me that universal norms about morality (what constitutes good), ethics (what humans ought to do), and logic (how minds ought to think) cannot be abstract and yet causally related to the physical world.

Abstract objects have the property of being non-causally related to anything else. To ponder Plato’s ancient problem, how can the universals ever connect to the particulars (down here)? The answer is that a maximally perfect and personal being exists that grounds the universals, and sustains the particulars.

Perhaps that was too philosophical. I’m saying that the three examples I’ve given imply a divine being that grounds ethics, morality, and rationality.

Normative logic presupposes a divine being, because to suppose otherwise reduces to absurdity. It’s no coincidence that most atheists maintain moral relativism, nominalism, and empiricism.

I read Machine differently to you guys.

What I see him as saying is that “reason” in an authority we accept as universal and binding, and which we cannot justify except by appealing to reason.

The conclusion of this argument is not that God exists, but rather that even those who reject God on the alleged basis of reason have to assume without any non circular reason some absolute authority over their thought.

Implicit perhaps is also the suggestion that many of the arguments against divine authority, or the authority of revelation could be made against the authority of reason. Both are ultimate complete absolute incapable of non circular proof and so on

I agree with Matt. Machine’s post doesn’t even seem to imply the topic under discussion now.

Perhaps (more on topic) a real “free thinker” questions religious authority, his sense of moral duty, the canons of rationality, the existence of other minds, etc.

There probably aren’t many real free thinkers out there, ay?

“So what is it you’re actually saying ? If we don’t believe in God then we belong in a Monty Python sketch because it makes as much sense ?”

Where does my post state, or even imply, such a conditional implication?

“logic is normative if it prescribes standards for thought and reasoning.”

Logic in and of itself is neither normative nor prescriptive. I must already have a set of logical rules and a conditional hierarchy of values running as control statements in order to assess the status of logic in relation to my thinking. So any normativity or prescriptiveness is purely a function of an already-accepted systemic notion of logic, combined with the set of conditional implications that parse my intellectual values in the process of my thinking, even in questioning such factors or evaluating their relations, legitimacy, and so on.

Consequently, any normativity, or prescriptiveness, obligation, or even duty, is simply the set of conditional relations ultimately based on my highest values. This conditionality includes relations of the form “if X is true, then I will do A”, which determines those actions I will take given particular antecedent truths. Whether X is God’s offer of salvation through believing in Jesus Christ or the principles of logic makes no difference: the relational evaluation process remains the same in kind.

For the record, I do believe in epistemological common ground with the atheist, but I do *not* believe that belief in God is the *direct* logical basis of the objectivist-rationalist atheist’s belief in the criterial ultimacy of reason. God is a corollary of this, but not logically necessary to function in relation to temporal immediacies as a finite rational knower.

Any criticism of this view, it seems to me, necessarily conflates the order of being with the order of knowing, and is simply unfair to the atheist. The atheist’s questions are about the order of knowing, or the legitimacy of various inferential moves in theistic case-building, and I respect that, even though it is true that there is a limited time in which to contemplate such issues due to the imminence of death, the possible consequences if one does not believe in God’s salvation, and so on. Hence, questions of logical validity concerning belief in God or Christ do not diminish the existential urgency of such belief, but they are nevertheless *not* questions about that urgency. Much theistic and Christian energy is wasted in conflating these two issues.

Machine,

Are you a foundationalist? And would you agree that language is normative?

I’m not quite clear on what you’re arguing.

“In What Sense (If Any) Is Logic Normative for

Thought?” (link)

“The transcendental arguments for God’s existence undercut epistemic justification by showing that only a universal rational being can provide the pre-conditions for logical debate, empirical inquiry (which assumes the universe behaves with regularity), etc.”

I”m not sure if this is the position of the poster or merely the characterization of Van Til’s view or both. But it seems to be self-contradictory in that if such transcendental arguments for the existence of God undercut epistemic justification per se, then there is no need to show this, since showing it is itself, ipso facto, an epistemic justification nonetheless.

Keep in mind that I *agree* that, metaphysically, only an ultimate rational being could provide the conditions of knowing etc., but that’s not the atheist’s question. The atheist’s question is about logical procedure: namely, precisely how one can validly reason to the conclusion that such a being exists as the only possible provider of such epistemic conditions.

I hope it’s clear that when I refer to logic as normative, I mean as in a normative science whose intention it is to determine what good reason is.

Machine,

Van Til and Plantinga are making epistemological arguments. The very question “what justifies belief in God” requires some prior concept of justifers, belief, intentionality.

Plantinga is a reliabilist, so he is not likely to be of much aid to an atheist that you describe, who is interested (as an evidentialist) in the inferential moves. I agree with your sense of urgency, but also think it’s important to note that the eliminative materialist position precludes intentionality. So should we accommodate that atheist’s questions for evidence about belief in God, or explain that an atheist already believes something that presupposes the falsity of naturalism: namely, the proposition that one can believe in anything.

“I”m not sure if this is the position of the poster or merely the characterization of Van Til’s view or both. But it seems to be self-contradictory in that if such transcendental arguments for the existence of God undercut epistemic justification per se, then there is no need to show this, since showing it is itself, ipso facto, an epistemic justification nonetheless.”

I’m pretty sure we misunderstand each other here.

When I say “undercut” what I mean is, it avoids the usual epistemological approaches to justification: basic beliefs, reliable cognitive faculties, coherence internal mental states, etc.

The essence of transcendental argument is that is takes something the skeptic already affirms and shows that the pre-conditions of that affirmation are God, knowledge of other minds, external world, etc.

I don’t see how this squares with your claim that this is contradictory.

“Are you a foundationalist?”

I try to avoid labels, but I’m not sure. I don’t believe that basic beliefs have any kind of non-inferential warrant, whatever that means. They are just there, and since they include implicit beliefs about the relation between such basic beliefs and things like survival, stable orientation to changing circumstances, etc., have no “more basic” factors to which they can possibly relate. As I’ve stated previously, it’s a package deal, and includes not only logic/reason but also relational and absolute values that are equally basic. I’m trying to build the inventory of necessary assumptions, starting from “I exist” and working backwards in terms of inferential derivation, but this project is in a very preliminary stage.

And would you agree that language is normative?

It is within it’s own rules, but there’s a normativity about using language as a system, which we assume in using language in the first place. So there’s an infrastructural normativity in the nature of both logic and language, but I don’t think that’s what you’re referring to in the question, so I would say no.

“In What Sense (If Any) Is Logic Normative for

Thought?”

I do not believe logic is normative except as an already-valued system of propriety about inferential relations among predications etc. One must already believe that one “ought” to think logically in order to make any first move in logical thought, at least as a means to achieve some goal or pursue/maintain some value. I get to God by means of recognizing logic’s separateness from myself in being necessarily *referenced* as an ontologically distinct and reliable object immune to the vagaries of the rest of my conscious awareness, combined with other factors such as my implicit criteria for personhood, the fact that criterial objects have no existence apart from some mind that thinks them, that no finite mind could guarantee perfect actualization of logical-rational standards, and so on.

Well, it’s a tricky distinction, but I think if we keep going we will reach some clarity here. To wit:

“the pre-conditions of that affirmation are God, knowledge of other minds, external world, etc.”

Again, those are *metaphysical* (or existential, if one prefers) preconditions, not epistemic ones. And again also, I *agree* with that statement. The problem as I see it is that the skeptic or atheist is asking a question about logic, not ontology or metaphysics. And this is why I don’t think it undercuts epistemic justification. Otherwise, I could say that that metaphysical priority argument *itself* contradicts its own elimination of normal epistemic justification, because it is still nevertheless an epistemic argument, regardless of the particular component terms of its premises.

Can you hold a justified belief about the external world, without the prior justified (or basic) belief that the external world exists?

How is this metaphysical but not epistemic? It seems to me both.

“Can you hold a justified belief about the external world, without the prior justified (or basic) belief that the external world exists?

How is this metaphysical but not epistemic? It seems to me both.”

Logically, a justified belief is by definition dependent on the justifying statement or statements that premise its justification. But it is the prior belief or assumption that directly justifies it, not the facticity itself per se. Otherwise, premises would not be needed for anything, just some kind of unstateable and unspecifiable brute reals, indistinguishable from each other, or from anything else, such as whim or heartburn or square circles, or nonsense factors such as the famous “blik” of the verifiability criterion of meaning.

The key distinction is between a belief’s being true, and *knowing* it to be true. The atheist is asking how one knows that God exists, not whether or not God does in fact exist. Otherwise, no argument would be necessary, even for the believer. The consistent response to both atheist and believer (say one who is in doubt, for example) would in that case always be simply “God exists”, and anything else would be epistemically superfluous, including statements about how God’s existence is the only possible condition for knowing, etc.

“Only assuming logic and reason makes logical priority possible and necessary, so there is nothing possibly logically prior, in the sense of more inferentially basic, if logic itself is questioned.”

This sentence doesn’t make any sense.

Machine,

Check out this article on transcendental arguments:

http://www.iep.utm.edu/trans-ar/

I still don’t think we’ve gotten at the issue here. Take this simple model of evidentialist justification:

A believe B is justified only if B1 is justified, where B1=the belief that B is supported by evidence.

But now B1 is justified only if B2 is justified, where B2=the belief that B1 is supported by evidence, etc.

Basic beliefs (other minds, external world) provide a stopping condition for what would otherwise be an infinite regression. Therefore, basic beliefs are *epistemologically* prior to the beliefs that inferentially flow from them.

I am sympathetic to your point about what atheists are asking for. They want to know how the belief is justified…they want evidence. But, in philosophical contexts where global skepticism and such are actually on the table (let’s be honest, no ordinary skeptic doubts that he has hands), it is very much necessary to show that some beliefs presuppose others. If the skeptic doubts his hands, but believes that he can hold a hammer: we should explain to him that his belief that he can hold a hammer presupposes that he has hands. Thus, he must abandon one of those beliefs. (I made that example up, it’s probably not a good one)

Well, that is what atheists are questioning: namely, in the case of your argument, exactly how does any thought whatsoever presuppose the belief that God exists, or what is the precise argument for this? I believe that atheistic criteria implies God’s existence, but does not directly presuppose it.

“Only assuming logic and reason makes logical priority possible and necessary, so there is nothing possibly logically prior, in the sense of more inferentially basic, if logic itself is questioned.”

Meta-philosophy is full of puzzles like this. Read those two articles, those guys are way smarter than me. Trust me, if it was as simple as “logic is ultimate, and you can’t prove otherwise”…these guys would have moved on to something more exciting. Stimulating discussion though, enjoyed it!

Well, they ignore self-reference in a number of instances, so something is missing from that picture. Nine senior-level courses in philosophy last year and self-reference was never even mentioned, and yet all of the 30 or so thinkers covered had serious self-referential issues in the material covered. This is at a major university.

Similarly, at the second largest philosophy department in the country, it is politically incorrect to have a debate, and it’s been this way for decades. The closing down of entire philosophy departments in the U.S. may be a kind of intellectual kharma.

“A prior question is why should there be *any* universal normative statements at all, if there is no God?”

I assume this means what are the reasons for any universal normativity if God does not exist.

My question is what are the reasons for being obligated at all, God or no God. What does obligation mean in relation to God, beyond the possible desirable or undesirable consequences either built into the cosmic process or through some kind of direct intervention by God. If it’s just cost-benefit, does this really change anything? In the case of an ultimate being who could mete out ultimate benefits or undesirable consequences, such calculation seems just as serious an issue as the traditional terms connote.

Dear Machine Philosophy, You know all there is to know about “God” and about “reason,” and everyone who doubts what you’re saying has no basis to even question it? Ha. Double ha.

I daresay, get your nose unstuck from Van Til and Bahnsen and read more philosophy, because it’s more lively and controversial than you seem to be aware of. There’s fascinating discussions CURRENTLY going on concerning the nature of logic, non-classical logic, logical pluralism, paradoxes, vagueness, contradiction, liars and heaps, new essays on the a priori, the origins of reason, the origins of objectivity, epistemological problems of knowing, empty names, shadows, holes, the law of noncontradiction, transconsistency, learning, development and conceptual changes, etc. These are all being CURRENTLY debated along with Philosophy of Mind, and Philosophy of Language. http://amzn.com/w/3UHOTPR7A2NU0

I daresay there’s far more discussion going on that you seem to even be aware of, and all our present knowledge is incomplete. Study Godel’s incompleteness theorem for starters. And consider the limitations of the senses, and the shortness of time we each have (indeed that humanity has each generation) for study and experimentation, and the uncharted vastness of the cosmos in both time and space.

As for “logic,” it’s based on pre-logical recognitions, logic does not appear to come before such recognitions but after them. For instance many animals with small brains perceive the difference between rain and sunshine, A is not B, and animals function naturally.

Dear Machine Philosophy, to clarify, I am not an atheist but agnostic. I admit I don’t know any absolute philosophical proofs though I have sought after them. The big questions remain mysterious to me. I don’t know how the cosmos began, nor if this is the only cosmos that was or will ever be. I don’t know where or what I was before I was born. I am unsure what will happen after I die.

But even presuppositionalist Christian apologists like Van Til admit they can’t prove things to people with different presuppositions, so at best it seems to me that a presuppositionalist apologetic can help someone maintain their beliefs, but not necessarily prove the truth of their beliefs to others.

I know the argument from reason, I’ve run across many variants of it as well. Van Til, Bahnsen, Plantinga, Hasker, Lewis, Reppert. And I accept that it convinces you. But have you considered just as deeply the presuppositions that naturalists hold?

There are different types of atoms, and different properties when atoms are combined in the form of molecules, and when molecules form chain reactions that take place inside organelles inside cells, tissues, organs, right up to the electrochemical impulses in one organ in particular, the brain, and the sensory organs that gather into the brain sights and sounds of entire environments in one big gulp.

Brains react to macro-sensations of environments, whole sights, sounds, words, feelings, etc., all of that being stored as conscious and unconscious memories and also as learned patterns of behavior, and those are constantly being tested and modified via feedback loops, i.e., constant interactivity with the environment and other living organisms.

Cut off a person’s external sensations/feedback loops long enough, such as in a sensory deprivation tank for months at a time, and the person can go mad.

And speaking of ethics, organisms if they are human (including many non-human species), agree that they don’t like having things taken from them without their consent, they don’t like being murdered, stabbed, robbed, called names. Some humans do exhibit horrendous behaviors, even psycho behaviors. But most do not. (Any species from bacteria to humans that did exhibit “nothing but” such behaviors would probably go extinct.) Instead, most people band together and agree that people who do things to others without their consent should be kept away from everyone else. They also agree it’s wise to start teaching young children simple rules of behavior, and a little later teach them the benefits of being a member of society and of doing to others in that society as they know they would like to have done to themselves. I’m personally in favor of teaching children in public schools all the practical moral wisdom of the world.

One presuppositionalist told me recently that “Morality does not exist without an overarching/transcendental immutable Being, just dislikes and likes.” But the naturalist presupposition is that human likes and dislikes are exactly the basis for human morality, since most people like being liked and hate being hated. We share similar pains when beaten without our consent, or stolen from, or called names. We share similar feelings when we share our sorrows and our joys with each other. We are a social species and so are other large-brained mammals of sea and land. And the same that is true individually is also true communally, hence the agreement to teach certain things as “laws” and to punish certain behaviors.

My presuppositionalist friend added that “likes and dislikes” were nor moral but inconsequential such as liking or disliking “pickles.” But that example is turned on its head by naturalists who can confirm that far more people agree with far greater urgency that choosing whether or not to eat a pickle is nothing compared with how the vast majority people agree concerning their dislike of beaten to death by one, without their consent.

So in effect, the argument ends there. You have your presuppositions, naturalists have theirs. Luckily there is enough of an overlap of appreciation for civil behavior as a whole between inerrantist Christians and atheists such that both can live together in a pluralistic civilization, hopefully without literally beating up each other, i.e., only tossing philosophical presuppositions at each other.

CONCLUDING POSTSCRIPT (from my online mega-essay here: http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/ed_babinski/experience.html )

The “human story” is old and brimming over with “influences” stretching back to ancient civilizations both East and West. In Western civilization alone there were ancient Near Eastern influences; Greek/Roman politics, art, architecture, law, science and philosophy; Eastern Orthodox and Islamic mathematics, astronomy, philosophy (including thousands of Greek and Roman manuscripts preserved by Islamic scholars at the library of Seville that played a crucial role in re-igniting Western society’s intellectual progress). Other major influences include “guns, germs, and steel;” the Renaissance; the Enlightenment; modern day socialist, humanist and feminist influences and ideals; and “common sense” (as Thomas Paine might say).

Speaking of the crucial influence that the Enlightenment exerted upon Christianity, theologian Albert Schweitzer pointed out, “For centuries Christianity treasured the great commandment of love and mercy as traditional truth without recognizing it as a reason for opposing slavery, witch burning [heresy hunting] and all the other ancient and medieval forms of inhumanity. It was only when Christianity experienced the influence of the thinking of the Age of Enlightenment that it was stirred into entering the struggle for humanity. The remembrance of this ought to preserve it forever from assuming any air of superiority in comparison with thought.”

Even Robert Wuthnow, an evangelical Christian writer, admitted in Books & Culture (a newsletter produced by the editors of Christianity Today), “Framers of modern democratic theory in eighteenth century Europe [and colonial America – ED.] were profoundly influenced by the religious wars that had dominated the previous century and a half. Locke’s emphasis on tolerance and Rousseau’s idea of a social contract were efforts to find unifying agreements that would discourage [sectarian] religious groups from appealing absolutely to a higher source of authority. The idea of civil society emerged as a way of saying that people who disagree with each other about such vital matters as religion could nevertheless live together in harmony.”

Wow. I’m really glad I asked the question and I almost followed most of what was said 🙂

What you’re proposing seems to be a two stage process – God exists, and that God is the Christian God.

Even if I accept the former I do not see how it is possible to accept the latter, particularly given it’s claim of exclusivity given the parity of evidence and/or grounding for other Gods.

Have you guys seen http://www.proofthatgodexists.org/ ?

Ed and Paul, you guys appear confused. Machine Philosophy is not a presup. Neither am I actually, we are just debating whether it is coherent.

Machine Philosophy,

I think Van Til agrees with your notion that you can’t “prove” the laws of logic without being circular. However, what he is saying is that the laws of logic are a certain kind of thing; in Bahnsen’s debate with Stein he called them “invariant and universal” or something like that. I agree with you,this sounds more metaphysical. It sounds like he’s saying that the atheistic universe can’t house furniture such as invariant universal laws. Van Til is very much about revelation. We would be stuck in our own subjective cradle, had God not revealed himself. It does little good to say that the laws of logic are universal because the must be so. Perhaps a different kind of evolved human brain would be apprised of different laws of logic.

“What does obligation mean in relation to God, beyond the possible desirable or undesirable consequences either built into the cosmic process or through some kind of direct intervention by God.”

I think the idea that illogical thinking often leads to undesirable ends is important; but ultimately, the obligation for the Christian to be logical derives from being created in the image of God. Right?

“You know all there is to know about “God” and about “reason,” and everyone who doubts what you’re saying has no basis to even question it?”

I don’t know of anything in my post or comments that even hints at this, unless of course someone has meta-prelogical-recognition trans-theoretic logic that could somehow know this from a self-exempted vantage point without any specific basis or analysis of my actual statements.

If I were going to make such a claim about someone else’s statements, I would actually quote exactly what it was that stated, implied, or suggested this.

Oy vey Machine!

Plain language might help communicate to a mixed audience here. Apologetics doesn’t work if they can’t interpret it. 🙂

“ultimately, the obligation for the Christian to be logical derives from being created in the image of God. Right?”

I just don’t believe in nonlocal obligation relations, unless it means nothing more than observing and acting according to the possible consequences. To think logically is on pain of the possible consequences of not thinking logically. I don’t think there’s anything more to it than that.

But that’s enough. In the case of believing in Christ, this is based on avoiding a possible consequence of endless misery if I don’t believe, combined with the fact that I could die at any moment and therefore must live with some view about this in spite of limited knowledge and relative certainty, that there are a number of opposing and alternative views to claims about Christ, interpretations of the biblical texts, historical testimony, the possibility of atheism, scepticism, and so on.

But back to the original point: I don’t have any obligations that do not run on top of my tacit assumptions about what to think and how to act in relation to my hierarchy of values that are already accepted in the mundane background of living and thinking per se.

Hopefully it is clear that this is why I do not negate the atheist view at the immediate operational level. I started out an atheist, and believed in Christ from the standpoint of having come to a belief in God from a default atheism (the mere lack of belief instead of a consciously maintained assertive negation of belief in God), and then surveying the possibilities beyond that belief, proceeding on the basis of a saving notion of rationality, throughout this entire process.

Anyway, for a Christian or nonchristian, any obligation to be logical is purely a function of a situated grasp of logic’s instrumental necessity in relation to one’s highest values, including but of course not limited to one’s survival in the here and now and projected possibility of survival in the more distant future.

“I hope it’s clear that when I refer to logic as normative, I mean as in a normative science whose intention it is to determine what good reason is.”

The normativity entailed by the use of logic already assumes what good reason is, otherwise it could not function as a tool of evaluation in the first place. And since logic is a set of general universally-applicable rules of thought, its use thereby already assumes a morality of thought.

I agree with the comment about plain language, and a substantial amount of my phraseology is geared down for this reason. But it has to be without any loss of essence and I’m not good at doing so without dialogue that forces me to distill my thinking into simpler prose. So I’d have to be given specific instances to know where to work out additional clarity and simplicity.

Another post said “This statement does not make any sense”. Not sure how to make sense of that statement itself either, given the complete absence of a single specific instance of how or why this is the case.

Often I suspect the beginnings of The Troll Sequence, which I’m going to outline fully in another post’s discussion, although I sometimes engage it. I’m not saying that’s what’s going on here, but for those not familiar with The Troll Sequence, here are some characteristics steps in the generic:

1. Begin by insinuating a lack of sincerity, posturing as clever, being a know-it-all, on the part of the poster.

2. Mention other philosophers and philosophical issues, and claim that the poster is unaware of what’s going on, etc., as if this is substantial to the issue in the thread.

3. Don’t quote or be specific, just make general claims and/or accusations.

4. If your bluff gets called, dismiss the whole case of the poster, or allege that they take themselves too seriously or think more of their own abilities or understanding than could possibly be warranted, or that if they don’t understand their own mistakenness then obviously no one could ever explain it to their satisfaction, and then declare the discussion over because of this.

I believe the comment originally addressed in this response was David P, and these last comments in no way apply to that poster or his comment.

“To think logically is on pain of the possible consequences of not thinking logically. I don’t think there’s anything more to it than that.”

Very interesting Machine. Would love to see you flesh this out (apologetics, Christian knowledge, etc) in future posts.

I’m pretty bad at plain language myself…I sometimes ask my wife to read my papers to see if I am making my point clearly enough. 🙂

“..unless of course someone has meta-prelogical-recognition trans-theoretic logic that could somehow know this from a self-exempted vantage point without any specific basis or analysis of my actual statements.”

I was sure I had one of them in my sock drawer last Tuesday. It was blue and smelled a bit like garlic? Likely it was something else, I swear, I’d lose my head if it wasn’t screwed on.

What I mean about logic is that I use it as a necessary means of parsing out possibilities in relation to various actions I might take or as a means of determining what to believe. But in relation to what to believe about logic itself, I might use logic in part to figure that out, but only in relation to a seemingly necessary but metalogical grasp of what value logic has, even in reviewing that value, whatever it may be. But in strict logical terms, there simply is no logically prior argument that does not use logic in the premises and therefore itself commit a logical fallacy in the process.

In the future I’ll be assessing John Dahms’ “How Reliable Is Logic?” and the quite aggressive debate that ensued with Norman Geisler, in a series of articles that appeared way back in 1978-1979 in the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society. Not sure if the entire thing is available online for just anyone (I got access through the university’s online resources, jstor I think it was.) But this will clarify my views on the philosophy of logic, and perhaps thereby flesh out some of these issues we’ve been discussing.

“What I see him as saying is that “reason” in an authority we accept as universal and binding, and which we cannot justify except by appealing to reason. ”

I appeal to experience personally.

The fact that one *appeals* to experience shows that reason is necessary to give experience justificatory status.

nonsense.

I’m wondering why appeals to experience must suddenly become appeals to alleged defections from the rational ideal, just as soon as the experience doctrine itself is challenged.

Experience is a necessary factor in knowledge, but reason must distinguish it from abstract objects and other cognitive elephants already in the room.

Well I guess technically speaking you need “reason” to know that whenever I eat something I stop feeling hungry… but you certainly don’t need a complex theory of knowledge to do this.. in fact cats can manage this… so perhaps no reason is needed at all.

Similar situation.

Pfft, come on m, tell the truth! You know that there’s a little angel on one shoulder telling you that you’ve had enough and a little devil on the other telling you to just have one more bowl of delicious ice-cream and pie!

Cats are not making appeals, which is the point in question. Any appeal to a rule-relation with regard to experience in general, as the justifier of claims, thereby assumes a theory.

Oh, okay, I think I’m getting the hang of this.

Machine Philosophy is proposing some kind of philosophical irreducable complexity!?

“Any appeal to a rule-relation with regard to experience in general, as the justifier of claims, thereby assumes a theory.”

But m isn’t making an appeal, he’s making an observation. and not about general experience but about particular ones, his and cats hunger abatement techniques.

Nevertheless I think that we can, and do, automatically infer an appeal to general experience, vis a vis hunger abatement,thereby assuming a theory by induction that life fulfils at least one purpose.

And I still think that sentence which I said makes no sense, isn’t a complete sentence!

“get your nose unstuck from Van Til and Bahnsen”

Everything I”ve said about Van Til’s view, except for the mere metaphysical conditional of God’s existence being the existential ground of knowing, has been *against* Van Til’s claim that the metaphysical ultimate, God, is somehow epistemologically primary, which to me is logically a category mistake and disingenuous with regard to the very nature of the atheist’s question.

Concerning Bahnsen, the only thing I’ve read by him is the first couple of paragraphs in his debate with the consensus-reductionist Gordon Stein, so I”m not sure where that connection came from or even why it would make any difference in the issues as discussed.

I am much like my cat when it comes to reason. I did a whole two maths degree and used the faculty of reason to solve some pretty damn complex problems without having to possess some theory about why reason worked…. it just did work. I kept using mathematical reason and I kept getting passes in my papers. It was pure observation. I don’t need some complex justification, or some wanky argument to prove that reason provides results over and over again. And quite frankly nor do any of the other six or seven billion people whether they have done a lot of maths or not.

The idea that you have to justify reason before you can trust it is farcical and once more my cat has shown itself to be smarter than “Machine”

“The idea that you have to justify reason before you can trust it is farcical and once more my cat has shown itself to be smarter than “Machine””

My entire post and comments have been about how reason and logic *cannot* be justified by their own use without fallacy and arbitrary self-exemption.

Where are you getting the idea that I have been arguing that “you have to justify reason before you can trust it”?

its not an “arbitrary self-exemption” though as I said. Ask my cat and he will tell you the same thing about hunger and all the other tools he uses from day to day. You are the one trying to make reason an exception amongst out tools which has some special situation

“My entire post and comments have been about how reason and logic *cannot* be justified by their own use without fallacy and arbitrary self-exemption.”

Shennanegins!

Using the logic and reason to justify God and God to justify logic and reason is just as circular as using the Bible to justify God and God to justify the Bible.

Basically you are trying to disarm your opponents, who are denying that your claim of the very ‘higher power’ you seek to justify logic and reason with, is itself justified.

What is ‘the atheist question here? Is it, “Where is God then, and why is HE hiding from me?”

Inquiring minds want to know.

“How can one believe in normative logical operations sans a universal mind? You can’t. ”

Many atheists do in fact believe in normative logical operations, but do not believe in a universal mind. If this is somehow a logical confusion, I’d like to know exactly in what sense this is the case.

In other words, why must there be a universal mind in order to buy into, and use efficaciously, logical operations and the implied normativity within an overall logical system, as the rationalist or objectivist kinds of atheists obviously do? I will expand on this in my upcoming positive case for atheism, but would like to address therein any defense of the necessity of a universal mind for the possibility of logical normativity.

To argue for reason is to use reason in the premises of an argument. This is the basic fallacy of logic, namely petitio en principii, or begging the question. That is, to use reason in the premises contradicts the supposed questioning and consequently a logical defense of reason. If reason really is in question, using reason to defend its use as a standard of thought would not be possible. If reason or logic are in question, one can hardly “support” them by simply acting as if they are *not* in question by simply using them nonetheless. If this is allowed, then, in the absence of some kind of self-exemption, any claim can be proved by merely using he claim as a proof of itself, and that by following the example of this same kind of bootstrap defense of reason. Reason can hardly be a exemplary standard of all thought, if that reason itself can get away with self-justification but somehow prohibit this for all other views, claims, and notions. Moreover, that kind of self-exemption would mean that reason and logic are not really universal after all, in addition to not having to have something besides themselves to prove their legitimacy as determiners of the truth or falsity of everything else.

Machine,

There is a family of apologetic arguments known as the Arguments from Reason. The first stage in this type of argument is to show that rationality is fundamental to reality. It then proceeds to modus tollens certain naturalistic claims.

For instance, if eliminative materialism is correct then there is no such thing as mental causation. Only physical causation is a proper explanation. Brain states do not cause other brain states. But what kind of rational inference is there without mental causation?

1. If EM, then there is no mental causation

2. There is mental causation

3. ~EM

You can do the same thing with intentionality, dualism, etc.

Reppert:

“So it seems clear enough that one cannot accept both a materialist world-view and the claim that someone has reached the conclusion that materialism is true on the basis of argument only if mental states exist as a matter of physical structure. The difficulty with this suggestion is that in reasoning the mental states involved are supposed to be connected by logical necessity, but one cannot given an account of this logical necessity by describing contingently connected physical states. ”

http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/victor_reppert/reason.html

I should note that this is an older version of his argument, and it has been modified a bit since then.

There is more info via Mr Google available.

You will also want to check out Plantinga’s Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism, which gives a defeater for the belief that naturalism is true (and all other beliefs) under certain conditions.

You’re being rather simplistic. Laws don’t have to be universal…they didn’t just fall in our lap, and we don’t have to assume they are universal. We define them as givens…but that amounts to nil.

Most atheist look at “logic” as a functional description of what human brains do. It’s the same thing as digestion in the human stomach. There is nothing universal about digestion or logic on the materialist’s view of the mind.

Check out Paul Manata’s debate with Dan Barker is you have time. It’s demonstrative of the two sides on “what logic is.”

It does not good to beat anyone over the head with truth tables….yes they are true and must be true because they are truth…but that means nothing if our minds are purely physically determined brain states with no mental causation, intentionality, or persistence over time (oops a tiny part of me just fell off, am I still me?).

Guess you really ought to ask them. Are you trying to steer atheists away from this or towards it?(and thereby towards a ‘compelling reason’ to believe?)

Gotta tell ya, I’m not ‘feeling’ it.

“Most atheist look at “logic” as a functional description of what human brains do. It’s the same thing as digestion in the human stomach. There is nothing universal about digestion or logic on the materialist’s view of the mind.”

Which is exactly what my cat has been trying to tell Machine. The apologetic strategy is to elevate “reason” to an almost divine status and then use this as proof that THEREFORE there must be a divine mind… the problem is very few atheists would accept elevating anything to a divine status in the first place. So Machine’s argument is a great way to preach to the converted – but has zero weight for anyone who does not already accept his world view. (please feel free to insert a wanky Latin expression to summarise this fallacy here if that sort of thing amuses you)

By definition reason is reasonable. So what?

“logic” as a functional description of what human brains do.”

Is this statement just brain activity or is this “true” about logic in the sense of being something about logic itself and not mere brain activity?

“few atheists would accept elevating anything to a divine status in the first place.”

Well, what would arbitrate that status without thereby being itself an ultimately-statused vantage point in order to declare what the status of reason is or should be?

What you are trying to do, “Machine”, in both of those comments, is force people to argue within your arena and accept your paradigm before any debate starts. But as someone already said this is as circular as that other apologetic argument of “the Bible says the Bible is true” which we fortunatly don’t hear so often now. Yours is however merely a (very slightly) more sophisticated version of the same thing.

If someone is going to make grandiose proclamations about what the status of logic or reason can or cannot be, I’m going point out the meta-logical, meta-rational supervisory status of those claims themselves.

It is those claims that are begging the question or self-referentially inconsistent or self-serving or all three, not my pointing out the implicit self-exempting that’s going on.

Claims about the status of logic or reason hardly qualify for a free ride. If they do, what other general claims can we just proof-text like they were some kind of unquestionable sacred text, complete with handy accusations of circularity for anyone who challenges them.

Reason works. It just does. We have thousands of years of experimentation and billions of eye-witnesses to this fact. Free ride indeed! I don’t really think this fact is in need of any rational justification (like some other claims are…) You are just playing silly games “Machine.” Everyone with eyes to see and ears to hear can see this.

David Parker, thanks for introducing the arguments about reason and materialism. I’ll be reading up on arguments by Reppert, Menuge and others, but am still doing a detailed analysis of Swinburne’s “Are Brain Events MInd Events?” article, a quite difficult essay. I’d have to examine eliminative materialism closely to have anything substantial to say about the argument you presented, but am sympathetic to its import. I do believe that mental (or more specifically, inferential) causation is arbitrarily left out of most discussions of causation proper, so if you have any suggestions as to the strongest sources for the type of argument you’ve referred to, I’ll definitely take a look. I will also read the debate you referred to.

I’ve never stated or even questioned whether or not reason “works” in this discussion. Perhaps you can provide examples of where anything I’ve said even touches on that.

The question is what the authority of reason is in comparison with the notion of God, and if it just has to be accepted similar to some kind of metaphysical article of faith, that’s a God-level status, with the same degree of immunity from criticism as the ultimacy and authority of God has ever been conceived of being.

If reason does not and cannot have any logical reasons to support it, then any appeal to the benefits of empirically-applied rational inquiry fly squarely in the face of one of reason’s own primary rules: premises cannot already assume or embody the conclusion. To try to demonstrate the ultimacy or reliability of reason is not only a fallacy of logic, but should not be required in the first place if reason really *already*—before such a proof has even begun—is believed to have universal authority to adjudicate *all* truth claims. The fact that people jump to the defense of reason with all sorts of appeals and arguments shows a reluctance to actually adhere to the dogmatic basicality that is claimed for it.

“Machine”: Bizarre word games! Nothing more.

Why does reason work? No idea! But It does – as shown by billions of examples!

Now you accept this as well as I do. But then you seem to think that because of this you can then elevate your “God” belief to the same level. But there is absolutely no link between the two whatsoever. You can’t just pick a random belief and say: “Gee! You can’t PROVE reason works – therefore I can claim X” Where X can be any random claim you want to make. Is this what passes for philosophy these days?! It is so laughable I just don’t know what to say about this really…

“Where X can be any random claim you want to make”

And where was this statement made by me, implied, or even hinted at?

No Machine. You were very careful. But this is the basic apologetic argument you are trying to lay a foundation for. The basic argument is:

Well you rely on reason and have no REASON for it.

I rely on God and have no reason for it.

You can’t attack me consistently until you can prove to me that reason is reasonable. The “X” in your case is obvious.

Where have I made such an argument? If i were going to make such claims, I would quote the exact texts, so that there would be no question as to whether or not the person in question made the argument.

Well so would I if it was a published journal article, or a book Machine – but this is a casual Blog so I am reading between the lines 😉

“The question is what the authority of reason is in comparison with the notion of God, and if it just has to be accepted similar to some kind of metaphysical article of faith, that’s a God-level status, with the same degree of immunity from criticism as the ultimacy and authority of God has ever been conceived of being.”

So then, obvious questions.

Did God create reason and logic? What would have God used in place of reason and logic to create things?

I think that you’ll notice where this is going, if you bother to answer.

The obvious. Reason and logic are not in the category of ‘things that need creating, or ‘things that need justification’, because they are self-evident.

Without reason and logic, all is chaos, all is confusion, from a thinking being’s perspective. And all we are talking about here is, from a thinking being’s perspective, after all.

Reason and logic are mental tools to avoid confusion, to make sense of the world around us.

As m pointed out, mammals, lizards, birds, insects and fish use them.

You want to attribute them to God? Fill your boots. Some attribute time marching on from second to second to God. So what?

How can we justify reason and logic? Simple.

We test it. We decide what the reasonable and logical thing to do is, and do the opposite, until we are convinced that reason is reasonable and logic is logical.

Wait a minute, we do that all the time, testing reason and logic against reality.(not ‘doing the opposite’, we’ll leave that to you MP)

Guess what? Sometimes, the most reasonable sounding theory backed by the most logical criteria sometimes turn out to not be the way things really are!

Reality is the final arbiter.

“You’re being rather simplistic. Laws don’t have to be universal…they didn’t just fall in our lap, and we don’t have to assume they are universal. We define them as givens…but that amounts to nil.”

I’m assuming this is directed to me. But if certain laws are not universal, then I’m not talking about them. If they use universal quantifiers without qualification, then I analyze them accordingly. To say that we simply define them as universal seems to involve a self-reference issue: namely, how one could reduce them thus without that reduction itself being a non-reduced universal about universals. In fact, it seems like it would also be self-reducing, with all the self-stultifying implications that would go with that. That may not be what you’re trying to say, but that’s my impression of the comment as stated, given nothing else to go on.

“Basic beliefs (other minds, external world) provide a stopping condition for what would otherwise be an infinite regression. Therefore, basic beliefs are *epistemologically* prior to the beliefs that inferentially flow from them.”

I agree with this, but to say that God is one of those basic beliefs is a conflation of epistemic priority with metaphysical or existential priority. And I know of no philosophical atheist who would deny that if God exists then of course the possibility of knowing and even existing is due solely to God as the ground of all being. But again, that is not the question the atheist is asking. The atheist is asking what is the argument that enables us to *know* such a metaphysical fact.

Also, I read the iep article and commented on it briefly, but you mentioned two articles. Or was there some other reference to those two that I missed somehow?

“What you’re proposing seems to be a two stage process – God exists, and that God is the Christian God.”

If this was directed to me, where in my post or any of my comments have I stated any argument for either? I stated that I think atheistic criteria imply the existence of God, but I believe that was a much later comment and regardless, I did not actually present any argument for it.

As Woody Allen once said, “You can’t disprove the existence of God, you just have to take it on faith.”

“What you are trying to do, “Machine”, in both of those comments, is force people to argue within your arena and accept your paradigm before any debate starts. But as someone already said this is as circular as that other apologetic argument of “the Bible says the Bible is true” which we fortunatly don’t hear so often now.”

Then show how my comments “force” this, and how they are circular. I don’t see how unargued claims further the discussion.

If you can’t see this “Machine” go re-read the comment again. It seems obvious enough to me.

“If you can’t see this “Machine” go re-read the comment again. It seems obvious enough to me.”

If that’s true, then you should have just said I should re-read my comments without any other comment on your part, if it’s really as obvious as you claim.

What’s obvious is that there is no way to distinguish your obviousness claim from sheer groundlessness of the allegation, but it does save you from having to back up what you say, while making criticism-insulated claims about others who somehow don’t seem to get the same benefit from your labor-saving obviousness doctrine.

You need to learn to write in a more natural style Machine. It is very cumbersome to read your comments.

“[I]n philosophical contexts where global skepticism and such are actually on the table . . . it is very much necessary to show that some beliefs presuppose others..

I agree with the last statement. However, at logical rock-bottom there is an operational inventory of statements (including definitions and other identities) that are interdependent within the overall system, and presuppose each other. You can verify this yourself by taking the statement “I exist” and asking yourself what assumptions are necessary for that statement to be true, meaningful, and so on. What is “I”? What does “exist” mean? What is meaning? What is a question? Why am I asking questions? What does “why” mean? What is the relation between my questions and “I exist”? “What is a relation?” “Why am I wondering about these things?” And on and on it would go.

Like many other things in life, this kind of project may seem hopeless or, in view of more psychologically, socially, or biologically basic or immediately needful issues, relatively unimportant. And depending on the situation, this might be so (Not everyone can devote a lot of energy to philosophical or even cognitive questions.). At any rate, it becomes quite daunting once one gets beyond a few dozen logically prior statements are added to the list.

But assuming one has the time, interest, and perseverance, it is still possible to build a list of statements that are necessarily assumed to believe that oneself does in fact exist, or to believe that the statement “I exist” is true, meaningful, properly assumed, and so on.

Now just as the most basic terms of such a set of statements are cross-defined, so each of the most basic statements in such a system assume all the others.

Having said this, I do not believe that we are *merely* a set of basic presuppositions or irreducibly basic assumptions or control statements, parsing sensation and code, but that is another quite different issue. But cognitively, that is in fact all we are.

Hi Machine Philosophy,

Sorry if I jumped the gun. You’re quite a polite fellow. At first I assumed your argument was based on others to which it had a certain affinity at least in my own mind. There is some relation, but it’s not exact. You do not appear to be attempting to prove the existence of God, but defending its warrant by comparing a belief in the a priori basis of reasoning with a belief in the a priori basis of God’s existence, and in effect claiming that non-theists have things that they also take on faith.

You wrote about “The ultimacy and decisiveness of reason,” and added, “There is nothing possibly logically prior, in the sense of more inferentially basic, if logic itself is questioned.” So reason is an unquestioned authority, much like the Christian “God.”

But here let’s consider some additional questions and add some further points. What is logic and reason? Do you imagine them to be nouns or things existing somewhere (inside the mind of God)? Are they prior to God, must God obey them (a sort of Euthyphro dilemma, but involving reason instead of morality).

Or are “logic and reason” verbs, i.e., productive tools of thought, dynamics of the thinking process?

And why do philosophers continue to argue over which argument/belief is the “most logical” and “most reasonable,” without coming to the same conclusions?

One basis for all “logical types of thinking” (logic as a verb) seems to be our recognition of separate things and of their relation to one another. The basic recognition that “rain is not sunshine” or that something is not some other thing, seems to be based on natural sensory-based recognitions. We can see and sense differences between things and also compare such things to each other. Such sensations and perceptions appear to be prior to more generalized comparisons that we call “logical.” That is to say that the history of logic may have begun with basic sensations, recognitions and distinctions that even animal minds are capable of making, such as, “rain is not sunshine,” and ends in the case of our large brains and their ability to generalize, as “A is not B.” Even more broadly, rain is not anything else but rain, or, “A is not non-A.” Such basic recognitions provide the ground rules for what we call logical thinking. But these are idiomatic truths, like the statement “1 does not equal 2 or any other number, aside from 1.” Just as in the case of mathematics, logic is idiomatic and functions on such a simple basis that computers can work out long complex equations in symbolic logic with far greater speed and ease than any human mind on earth. Compare that with the fact that it’s taken computer programmers far longer to get a computer to distinguish objects in the world of sights and sounds, such that the question of focus and concentration is a far more difficult one to work on than merely the question of “logical relations.”

—————————

Also, I’d like to know more about your atheism and what books you read that convinced you atheism was true, and later, what books you read that convinced you Christianity was true, and at what age. I’m curious. I edited a work titled Leaving the Fold: Testimonies of Former Fundamentalists and an online article, The Uniqueness of the Christian Experience (a response to Josh McDowell’s chapter of the same name, though Josh dropped that chapter and argument after ETDAV 1 and 2).

“defending its warrant by comparing a belief in the a priori basis of reasoning with a belief in the a priori basis of God’s existence, and in effect claiming that non-theists have things that they also take on faith.”

I’m not defending the warrant for belief in God, but only showing that 1) belief in reason and logic are themselves rationally and logically groundless, and 2) that both are as vulnerable to atheistic scepticism as the belief in God itself. This does not equalize their ultimacy and decisiveness in all senses, since we do not have to use the existence of God directly to function in the immediate locus of biological survival or social interaction. That’s part of why there is an issue with regard to God that does not normally obtain in the case of reason and logic. But there’s much more to the story, and I will address the other points soon.

Concerning the arguments of Reppert, Magnus, and others concerning reason (I assume this is what you were referring to comparatively), from what I’ve read so far, I just don’t see any possibility of success on the basis of explanatory adequacy or explanatory priority, but I could be wrong about this, and I only have a cursory knowledge of these types of arguments at this point. Craig once mentioned a similar thing about God being the best explanation of abstract objects, but did not present an argument for it and again I just don’t think it has any possibility of success. I’ll give them all a thorough analysis on this blog once I have had the opportunity to study them.

“1) belief in reason and logic are themselves rationally and logically groundless, and 2) that both are as vulnerable to atheistic scepticism as the belief in God itself.”

They may well be “rationally and logically” groundless – but as I have already pointed out the fact that we have:

(i) billions of eyewitnesses to the effectiveness of these tools

(ii) thousands/millions of years of experimentation where these tools have proved effective without fail

(iii) technology. culture and society built up using these tools.

MOST people would think this provided some grounds! So the faith we have in reason/rationality/logic is not groundless at all. You are just insisting on a certain sort of grounding for some reason.

Perhaps you can explain how you can argue for reason or logic without thereby committing a logical fallacy by assuming reason in the argument for it.

“Perhaps you can explain how you can argue for reason or logic without thereby committing a logical fallacy by assuming reason in the argument for it.”

See above post. I don’t ARGUE for it… any more than I ARGUE for the fact that I am hungry. Yes. Logic is a useful tool. It is not the only one. You know that saying about how when the only tool you have is a hammer everything starts to look like a nail? I think you have fallen into this trap “Machine.”

If it’s not an argument, then your facts are logically irrelevant to the issue in question. Otherwise, I have no idea why you’re trotting them out as if to somehow give credence to your position.

In terms of logical priority there simply is nothing that can be offered in defense of the ultimacy or decisiveness of reason or logic that does not by that process constitute the most basic fallacy there is: namely, assuming the conclusion to formulate an argument for that same conclusion.

“If it’s not an argument, then your facts are logically irrelevant to the issue in question.”

Again stuck on the same point “Machine.” You are obsessed with everything being reducible to some logical argument before it is admitted as evidence. But if I get up in the morning and go outside and feel the sun on my skin I KNOW it is a nice feeling and I am happy. I can’t logically demonstrate it to you – and nor would I want to. The same applies to my knowledge that logic is a reliable tool. It is demonstrated by direct experience. To ask me to “prove” this is like asking me to “prove” using logic that I feel hungry, or tired etc. You are committing a category error.

“Otherwise, I have no idea why you’re trotting them out as if to somehow give credence to your position.”

Of course, ironically, you don’t actually need my say on this as you also have access to the direct observations I have access to. You too know when you are tired. You too know that reason is reliable.

“In terms of logical priority there simply is nothing that can be offered in defense of the ultimacy or decisiveness of reason or logic that does not by that process constitute the most basic fallacy there is: namely, assuming the conclusion to formulate an argument for that same conclusion.”

You need a new tool “Machine”. Your hammer is not going to work here sorry 🙂

evidence, n.

1. A thing or things helpful in forming a conclusion or judgment: The broken window was evidence that a burglary had taken place. Scientists weigh the evidence for and against a hypothesis.

2. Something indicative; an outward sign: evidence of grief on a mourner’s face.

3. Law The documentary or oral statements and the material objects admissible as testimony in a court of law.

tr.v. ev·i·denced, ev·i·denc·ing, ev·i·denc·es

1. To indicate clearly; exemplify or prove.

2. To support by testimony; attest.

Evidence is either part or all of some argument, or else has meaning only in relation to some argument. So again you’re just confused about the meaning of your own terms as well as unaware of the very nature and self-referential constraints of meta-theory and metalogic.

“But if I get up in the morning and go outside and feel the sun on my skin I KNOW it is a nice feeling and I am happy. I can’t logically demonstrate it to you – and nor would I want to. The same applies to my knowledge that logic is a reliable tool. It is demonstrated by direct experience. To ask me to “prove” this is like asking me to “prove” using logic that I feel hungry, or tired etc. ”

I’ve discussed only reason and logic themselves, not first-order awareness of objects or feelings. The argument:

Logic is a means of proving claims.

Therefore, logic is a means of proving claims.

is a fallacy, the most basic fallacy of all fallacies in logic, as any textbook in logic explains. Logicians commonly call it petitio en principii, but it’s common name is called “begging the question”. It does not mean that we don’t or shouldn’t use logic to prove claims, but to try to prove it using itself is a fallacy specified by that same logic itself. Somehow you don’t seem to realize the procedural issue involved in pointing to scientific observation or some other direct sensing to somehow “demonstrate” logic, even though logic and reason are already being assumed in order to merely know that an observation relates to some issue or theory, or even distinguish a scientific observation from some irrelevant feeling of heartburn.

I’m a thoroughgoing rationalist of sorts, and all my posts and comments assume the ultimacy and adequacy of reason for purposes of arguing claims and explaining issues. But there is no logically prior argument for using logic and reason themselves, it’s just a situated grasp of their usefulness and necessity. I cannot *logically* defend logic or reason without breaking their own primary rules of logical and rational propriety.

So what refutes your attempts to somehow “support” the ultimacy and decisiveness of reason and logic is their own rules of inferential propriety, regardless of how intuitively, heuristically, and confidently we may grasp their importance and use in relation to our values and goals.

Hammer still ain’t workin’

Not sure where you got the vague idea that anything is intended to “work” here. Nothing I’ve said depends on you’re understanding anything, or believing that anything “works”. What “works” is precisely your inability to understand or think with any degree of logical precision, especially logical validity.

“So reason is an unquestioned authority, much like the Christian “God.”

That is correct, but the unquestionability of God is not my belief. It’s that of most who do believe in God.

If we believers in God are to honestly debate atheists, we must first admit that we are both already proceeding on the basis of a set of God-level criteria to which we necessarily refer as having the authority and the efficacy to hand down a decision about whether or not God exists. Consequently, both believers and atheists have some explaining to do.

This is laughable Machine. The “atheist” if all they have to “explain” is why reason works has nothing to explain at all! As I have pointed out already and you have consistently ignored – they have billions of eyewitnesses and millions of years of experimental data – the god-botherer has neither of these things. Your argument is a farcical. You keep beating this drum about having to prove something everyone EVERYONE is in no doubt about and compare this t something everyone does doubt. Laughable.

“The “atheist” if all they have to “explain” is why reason works has nothing to explain at all!”

And where did I say that the atheist had to explain “why” reason works? To say that someone has some explaining to do is not necessarily to say that one has to explain why reason works, nor have I made such a statement.

Or maybe you can show how reason works by actually doing some reasoning about this new unargued question-begging claim of yours.

“To say that someone has some explaining to do is not necessarily to say that one has to explain why reason works, nor have I made such a statement.”

Glad you admit this finally! But you still have yet to address the billions of eyewitnesses and millions of years of experimentation and explain why you reject this evidence because it does not fall within your narrow framework. But you are on the right track now.

“Or maybe you can show how reason works by actually doing some reasoning about this new unargued question-begging claim of yours.”

And now sadly off track again.

Now let me parody you:

MACHINE-FACE”

“So reason is an unquestioned authority, much like the belief that Max is the world emperor and Machine is a fool.”

That is correct, but the unquestionability of “Max is the world emperor and Machine is a fool” is not my belief. It’s that of most who do believe in “Max is the world emperor and Machine is a fool”.

If we believers in “Max is the world emperor and Machine is a fool” are to honestly debate atheists, we must first admit that we are both already proceeding on the basis of a set of “Max is the world emperor and Machine is a fool”-level criteria to which we necessarily refer as having the authority and the efficacy to hand down a decision about whether or not “Max is the world emperor and Machine is a fool” is true . Consequently, both believers in “Max is the world emperor and Machine is a fool” and atheists have some explaining to do.

In other words you can use the pseudo-claim that reason is in need on some sort of justification to magic into existence any bizarre claim you want – including that of the existence of a god. Weak. Weak. WEAK!

Not sure where you keep getting the idea that I”m saying that reason is in need of some sort of justification. I’ve never said that. Perhaps you could actually read the comments themselves and provide a statement-numbered logical argument with derivation tags for each step in the argument, and actually show this, using the reason and logic you seem so increasingly desperate to demonstrate by assuming them beforehand.

What you might want to do is ask any instructor in logic whether in terms of logical priority trying to give reasons for reason or use logic to defend logic is itself a strict logical fallacy.

Please stop beating the same drum Machine. It is getting dull. How about you actually address the issues I raise?

I have shown your whole point to be farcical and yet you are stuck on this whole thing about a logical fallacy which I am blatantly not committing.

To use evidence to prove reason is still assuming reason and the relation to reason on the part of empirical data, in that same argument. Which is a fallacy.

Don’t take my word for it. Anyone who teaches logic, as well as any logic textbook, explains this in the section on validity. If anything is beating the same drum it’s your conclusion, which is a repetition of what is already included in the premises. Hardly a valid argument at all, unless of course one actually avoids the study of logic and never talks about validity or fallacy in any kind of specific and precise way. Which is usually followed by someone starting to tell other people what to do. Like little gods.

“To use evidence to prove reason…”

Yes – but this is not what I am doing. I think you have interpreted what i am saying within your own framework rather than trying to see what I am really saying.

“Don’t take my word for it. Anyone who teaches logic, as well as any logic textbook, explains this in the section on validity.”

Just asked myself. Nope I am not committing a fallacy.

“If anything is beating the same drum it’s your conclusion, which is a repetition of what is already included in the premises.”

Given that (i) I have not presented an argument (which you yourself complained about), (ii) I have presented no premises, and (iii) I have not provided a conclusion to my none existent argument this seems an odd claim to make.

“Hardly a valid argument at all”